Between Man and Wolf

By Shura Burtin

April 26, 2010

Translation by Steven McGrath

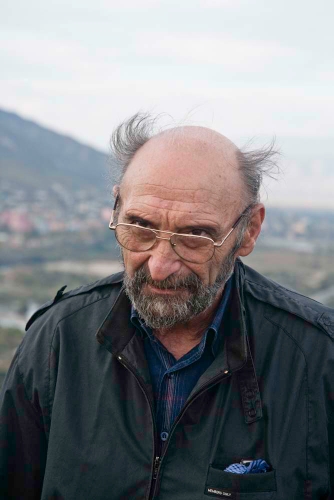

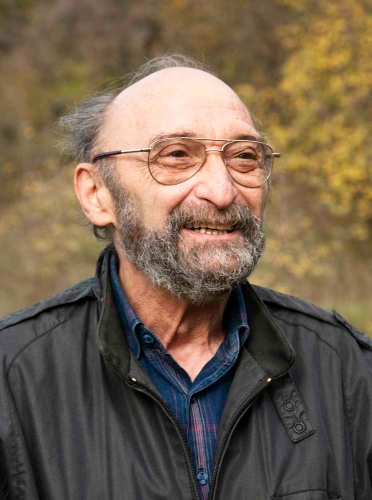

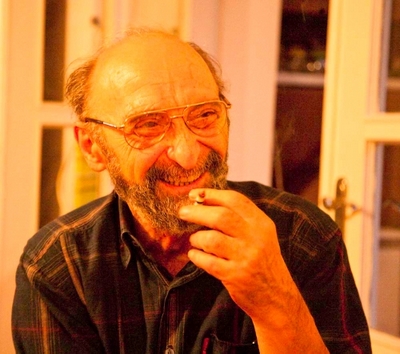

Misha Ioshoy (yazim) and I held an interview with Yason Badridze. It was, without a doubt, the best interview I’ve ever gotten. Yason is one of the most amazing people on Earth. He lived with a pack of wolves for two years and brought the attention of both of us to something important. He told us about the animal culture, and taught the wolves how to save themselves from us. Because Yason delves to the level of human consciousness that developed ancient myths where men and beasts could understand one another, it feels like nothing less than a fairy tale come to life.[Badridze]

-When I was five years old, in the autumn, my father took me to Borjomi Gorge. We stayed near the edge of the woods, from which strange noises were heard. When I asked about this, the lady of the house responded that the deer were wailing.

-Why are they wailing?

-Well, they’re wailing now, but there will be fawns come spring…

A child couldn’t be told why the deer were wailing. Well, as I had been told, children came from cabbage patches. So I thought: there isn’t any cabbage in the woods, so fawns must come from the bushes. I told everybody my opinion and they all started to laugh, which offended me terribly…

Then my father and I went into the woods and heard the howl of the wolf. That left such a frightening impression, it was amazing! I’ve taken all of that into my soul. Even now, whenever I hear a howl, I get kind of excited and want to run off somewhere. It’s hard to explain…As far as I can tell, that’s where it started. And when I had to decide what to do with my life, that’s what I chose.

-So, you lived with a wolf pack for two years?

-Yes, I started out as an experimentalist studying the physiology of behavior. But I soon recognized that we were studying mechanisms for which we didn’t understand the meaning. We hardly knew anything about the life of an animal in nature and very little had been published about wolves. I tried working on group behavior in dogs, but I quickly understood that, with them having lived so closely to humans, they had lost many behavioral traits. It was then that I decided to work with wolves. I went back to Borjomi Gorge and found a family of them. I was interested in how their behavior was formed and how they taught pups to hunt…

-Wait a second. How did you get acquainted with them and gain their trust?

-First of all, I needed to determine their main trails.

-How did you go about doing that?

-Well, having been an avid hunter since childhood, I was able to trail animals and draw a bead on them. And so, once I had found the trail, I got some old swaddling clothes (which my kids had outgrown) and dragged them along so my scent would become familiar. I also threw some of pieces along the path. It was of white material and contrasted well with the surroundings. Wolves have a well-developed sense of neophobia.

-What’s that?

-Neophobia—they fear anything new. But, on the other hand, they really want to study it, and this is an ongoing contradiction in their lives. The wolves started to circle these pieces from a distance. It was interesting to see how they gradually closed the distance before finally gnawing at the pieces. I then began to put chunks of meat in the same places. When they started nibbling at those, it meant they were already used to my scent. All of this took about four months.

-How did you get through all that time in the forest?

That was no problem: I had proper clothing, my rucksack and my mess kit. I didn’t bother with any tent. Whenever I needed to start a fire, I went across the stream. The air always moves in the mountains, so the smoke wouldn’t bother them. I already knew all their trails, and knew where their daytime resting-place, their rendezvous site, was…

-But you didn’t approach them yet?

-No way—I didn’t want to scare them. Later on, I decided to meet them. One morning I saw that they had passed—the elders of the pack, the alpha male and female. They were seeking a den for their cubs. I stayed and waited for them about fifty meters from the path. They returned around noon. When they saw me, the alpha female stopped in her tracks, but the alpha male came straight towards me. They came up to about five meters away and looked at me. I’m telling you, this was how close they came! When have you ever looked a wild beast in the eyes at such a close distance? I was unarmed, and he knew it, as he knew guns well by the smell.

-Why were you unarmed?

-Guns make men cocky. A man will take risks and make things more complicated because he knows that he has firepower at his back. I know that because I had an entire arsenal at home, and my father had a truly amazing collection. I’ve been well acquainted with firearms since childhood. Back then, my father taught me that there is nothing worse than running from a wild predator, because they will catch you no matter what. The alpha stood and looked, looked and barked, then turned around and went back to the trail. The pack calmly went on. It was as if my tongue had gone away, and I couldn’t move it. After that I was really home free. He had tested the way I would react. He had seen that I would neither attack him nor run away.

After that it became possible to go along with them. They would walk along, and I’d be about fifty to a hundred meters behind them. I ran after them with my hiking clothes, mess kit and all the stuff in my rucksack. My father had put me in the proper shape. He was the founder of a local mountain-climbers club, and, furthermore, I had done acrobatics from childhood. I was master of my own body and could jump and fall as I pleased. All the same, of course, it was hard to keep up. They wore me out, and, what’s more, ignored me for my trouble, as though I didn’t exist.

-That is to say, you managed to live among them?

-Yeah, I always went with them everywhere. I would lay myself down to sleep wherever they stopped. I slept with my felt coat wrapped around me on the rendezvous site. I once heard water burbling, and felt something running down my cloak. I looked up and there was the alpha with his leg lifted, finally noticing my presence in camp …

-So, tell us about the pack…

It was a wonderful family, the best ever. The most senior was an ancient wolf, and then the alphas, mother and father, three beta wolves (grown cubs of previous years), and then the cubs. The old wolf was already all hunted out. There was a small hill on the rendezvous site where he always lay keeping his lookout. The view was good and went far. A she-wolf brought him food—she regurgitated it after the hunt. Wolves have the interesting ability to control stomach secretions. If meat is needed for future use, or to feed an elder, it isn’t digested at all. It just gets covered in mucus. The mucus is antibacterial—the meat doesn’t spoil on the ground, at worst it’ll dry up a bit. They bring meat to the cubs half-digested about half an hour after the hunt. Thus, the alpha female and one of the beta males kept the old wolf fed.

That beta male, Guram, even fed me when I badly hurt my leg and couldn’t join them in the hunt. When the pack returned, Guram came up, looked me straight in the eye, and…hup! He vomited up some meat half a meter from where I was lying.

Guram was the name of my childhood best friend. We would climb the mountains together. He died, and so I named that beta in his honor. There really was a resemblance--the beta was so tall and had such a fair coat, much fairer than the others. He also had a good personality. Young wolves get into fights pretty often, and Guram always won them, though he never started them.

-And they all accepted you equally?

-The mature wolves accepted me after the first meeting, and the juveniles watched and followed their lead. They understood that I wasn’t dangerous. When the cubs were born, they had no idea that I wasn’t supposed to be there. What’s more, the wolves had seen me much earlier than I had seen them. While I was still tracking their trails, the wolves already knew me by body and face. They understood how my presence protected them from hunters. The poaching down there was brutal. People could get fifty rubles for a wolf, and they were always chasing them and setting out traps. I made a deal with the poachers not to touch the wolves while I was there, on penalty of butt-kicking.

-How do the wolves live? What do they do?

-They spend plenty of time resting. They need to minimize their energy usage. On breaks where the whole family gets together, they mostly lie around and look at each other. The alpha male and female might lick each other. The adults don’t play, but the young play a lot. Play, rest and hunt is all they do.

-Do they sleep by day or by night?

-You can never predict that, because it depends on the situation. If they’ve found themselves a good kill, like a big deer, they’ll feast. They’ll feed the cubs or the alpha bitch who doesn’t hunt after whelping. They’ll bury whatever’s left in hoards and might spend the next few days doing nothing.

-How were the relationships within the pack?

-Very good. The five of them looked after the cubs wonderfully. They all went up to the elder wolf, as well, to lick and groom him. The only problem was the determination of status. The young wolves are always scrapping with one another. At first they fight themselves bloody, but then they learn to ritualize their aggression. This happens at about one and a half years of age, when they enter the social system of mature wolves. Mature wolves also go into aggressive states, but this is ritualized. They can show their fangs and grapple, but they won’t leave permanent marks. That’s very important.

-How do they hunt?

-Well, often the elder wolf jumps up, sits on his hind quarters and starts to call to the others. They nuzzle each other with their noses. The alpha male turns and goes off about fifty meters, pricks his ears up and turns to maintain contact. Then they nuzzle again and look each other in the eye, as if they are coming to an agreement before going off on the hunt.

They go down the path, stop, look each other in the eye again, and then they all break up. They split the various duties of the hunt: some are better at running and the chase, while others are better at pouncing from an ambush point. Let’s say there was a huge meadow. The alpha female and her daughter would go off to the edge of the forest, while the alpha male attacked a deer and started the chase. Another one covered the path, so each was driving them ever closer to the edge, where the she-wolf would pounce.

-How do they agree upon who goes where?

-That’s just the point. There’s communication by sound, smell and sight, but there’s also some kind of non-verbal, telepathic connection. You can see that very well before the hunt begins. It’s like they’re having a meeting. They look each other in the eye with a peculiar fixed gaze. Then the beast turns about and does exactly the thing which seems most fitting for the moment. And when all the barriers between us fell away, this consciousness came to me as well. I was going out with them on the hunt, the alpha male turned and looked me in the eye, and I went to exactly the place I needed to be. After the kill, it turned out that I had cut off the deer’s escape route.

-And the deer couldn’t get off the trail?

- It’s very easy for a deer to get its antlers stuck, so going off the path is difficult.

-Did your consciousness bother you at all?

-At first it did, when I was thinking about what to do. Later, after a few months, it didn’t at all. By my ninth month there, I could describe in detail what the wolf behind me was doing. This came from a kind of tension: these were wild beasts, after all, and I needed to keep a degree of control. This tension apparently gave me some kind of third eye, or whatever it’s called.

Later on, I created a kind of experiment. I would train a wolf in a closed environment with light coming out of the right side and sound coming out of the left. The food was there in a bowl. Training required roughly ten experiments. After that, the animal would remain in the room, and we’d bring in a second wolf. It couldn’t hear or see the first one, I’m completely sure of that, because I had a microphone that felt vibrations from 5 Hz. to 35 kHz. There were no outside sounds. The second wolf was trained in five experiments. When you take out the first one, it takes ten or eleven. Why would that happen? It’s tied to food, after all. The animal gets nervous when it hears the conditioning signals and then, by all appearances, consciously does everything that it’s supposed to do. That somehow gets transferred…

Overall, there were a ton of questions that had piled up over those two years that needed to be answered by experimentation. All that experimental work was food for thought.

-Do they often manage to catch the deer?

-They’re doing well if they succeed in one in four hunts

-That’s not very often. Does it satisfy them for long?

-It lasts them a few days. As I’ve said, they hoard some away. On the other hand, it seems that the wolves forget about their hoards. What can they do about that? I did an experiment, and it seems that the function of the hoards is not for the wolves to feed themselves, but to create the most stable food base for their cubs. The odds of finding either their own or some other pack’s hoards are big enough that there is no reason to keep track of them. It is good that they can’t remember their own hoards, otherwise they would eat it all themselves when they need to keep it for after whelping season to stave off the cubs’ hunger. When the cubs go hungry, they grow up psychologically damaged and on-edge; their aggression never becomes ritualized, and remains deadly serious. When a she-wolf approaches her whelping time, the pack begins to intensively put away extra food. They bury it and forget it. That’s an unbelievable adaptation to fail to remember. It sounds absurd, doesn’t it? “Adaptation to fail.” But, that’s the way it is.

-Did you want to know how cubs are taught to hunt?

-Yes, all large predators teach their young how to hunt. They aren’t able to do that from birth. Weasels, for example, hunt for rodents. They are genetically determined to do that, and it’s what they do. Weasels don’t teach their young to hunt. Once a young weasel leaves the nest, they can hunt right away. A cub, on the other hand, might kill a rat and then straight away lose interest. It might die right next to the dead rat from hunger.

-Why is that?

- I think that there’s a big difference in the potential victims for large predators. They have certain inborn instincts, such as the reaction to the smell of blood and the need to follow moving objects, but this is far from any ability to hunt. If some untaught wolf fell upon a flock of sheep, it would go into panic. It wouldn’t understand that they were food. For wolves, hunting is a culture and tradition. Every pack has its own way. In some places, they are only able to hunt deer and elk. This is both a carefully adapted limitation to avoid competition over prey and a classic example of tradition. If a wolf cub is never taught to hunt elk, he’ll never learn. He wouldn’t even know the smell of elk.

In the place where we lived, there had once been an imperial hunting enterprise. Observers of the time described one unusual method of hunting among wolves. Usually they’d try to trip up a deer by running down the side of a hill, and the deer would try to escape by running upwards. This is an instinctive reaction for deer. It’s easier to save yourself by going uphill, as certain death awaits when going downhill. So here, the wolves would specially drive the deer uphill--and over a cliff. The deer ran straight off it, and the wolves would calmly walk around the mountain and find the corpse. The pack I followed used the same method at the same exact place while I was with them. All of this must be passed along from generation to generation.

-So they don’t even need to agree on how to do it, then?

-There are no absolute standards for this. Old experiences should be adapted to a new situation. That is to say, you have to think. I’ve always been interested in whether or not animals are capable of thinking. I created experiments for the ability to take old experiences into new conditions. All the wolves look different in the experiments, both visually and physically, but they are able to understand the logic of their assignment. Only extrapolate the change in movement by ten times, and you have a hunt. A beast can do nothing on the hunt without being able to think. They’re put on a pretty simple level, but they need to learn it. A zoo wolf can’t do it. But wolves can do much more: they can predict the result of their actions and act according to a common goal. I did the experiments, and I have the proof.

I further deduced that wolves can count to seven, and exactly seven. They often have to figure out problems with more than seven in the number, but they can’t do it. Well, it’s easy for them to find the third bowl in the fifth row, but beyond seven, they forget it.

They are thinking all the time. Whenever something works on the hunt, they start to adopt exactly that approach. If the deer goes into the bush once, the next time, it will be impossible. They learned this in one try. On the next hunt, they concentrate on not driving the deer into the bush.

-And how do they teach the cubs?

At first they bring chunks of meat. Next, they bring the chunks of meat with the hide still on it, which teaches the cubs the scent of the prey. It gets more complex as they age. The adults start calling the pups to kills at four months. When they’ve killed a deer, they call out with a howl and show them how it looks. Then, they teach them how to find a trail and track their prey. At first, the cubs don’t understand which way to follow an animal’s trail, but within a few days, they know how to do it correctly. If they manage to catch up, however, they turn around and run off. They continue to have an overwhelming fear of deer until the age of about nine months. When this passes, the young start to go on the hunt alongside the grown wolves. They start by simply running near the adults. They’re still very afraid, but gradually, they start to snap at the prey, and then pick up a proper approach. All of this is done in about a year and a half. Each wolf has its own approach to hunting, depending on strength and personality. Some go for the rump, others for the side. If a wolf is weak, it will choose a tactic which doesn’t require too much effort. If a wolf is cowardly, it will choose the safest route. They also take on specific roles: one chases, another herds, and a third pounces…

Beyond that, the cubs are always playing with each other. If you compare how a cub attacks during these games and how they do it later on the hunt, it becomes clear that they are very similar. They also learn to feel and understand each other. The cubs later hone these skills on real targets… They start small, with rabbits, and study the best way to get them carefully. There are no second chances with this type of learning, so each rabbit is a new lesson.

-Did the pack change in any way while you were living with them?

-Just that they drove out one of the yearlings. He had a difficult personality and always had some kind of conflict, so they kicked him out. Generally, an aggressive personality should become dominant, but if this aggressiveness crosses some boundary, the entire social system down to the lowest individuals unites and drives them out. It’s a kind of mechanism to control overwhelming aggressiveness. Such a beast can never find a mate. In this way, if there is some gene for aggressiveness, it is moderated.

-Where did the lone wolf go?

-Well, he went beyond the boundaries of our territory. Wolf pack territories never touch on each other, and each lives within its own system. There are at least two to three kilometers between each, which makes up a neutral zone into which individuals can exit. Families can’t go on reproducing forever, even with the one dominant pair, the alphas and their cubs. The beta females don’t even go into heat, as a rule. They have to either leave the pack or wait their turn while their parents age. All the same, the litters grow, and every four years or so things get too crowded. Every mammal group has its own limit as to the number of individuals within a social group. Once things go past that number, things start to shake up and conflicts start. They start to sleep further apart, which is the first indication of trouble. They usually sleep close together. Aggressive confrontations become more and more common, the distance widens, and cliques begin to form. The groups lose contact with each other, and eventually one goes away. The dominant group remains.

-Where do they go?

-Wherever luck may find them. If they go onto rival territory, they’ll be killed. Sometimes it happens that they unite with another group, if their numbers are few enough to allow more members. Often, they go into the human world and start slaughtering sheep.

Anyway, they drove off the yearling, and the oldest wolf died. As it so happened, this was all around the time the cubs started coming out of their den. Cubs are born in a den and don’t want to leave because of their neophobia. The den, however, is never at the rendezvous site, but at some other secluded location.

So we had all gathered at this spot, and everyone was there except the old wolf. I awoke at daybreak to the sound of whining cubs. The cubs were hungry because their mother hadn’t fed them in nearly a day. She would just take a quick glance at them, then go back and lie at the mouth of the den. The oldest sister did the same. The others sat around in a circle, waiting tensely. I had watched them waiting for something since the day before, and they were clearly very worried about it. This went on another four hours that morning. Finally, the cubs’ lovely little muzzles poked out of the lair. That was an emotional moment. I recall catching myself yelping with delight along with the others. The mother crawled up to them, licked them and turned back around. Then the cubs’ minds were made up. The little ones left that place, toddling after their mother and clinging to her. Everyone circled around the cubs and had a good sniff.

Suddenly, we heard an awful, spine-chilling howl. It was clear that something terrible was happening. We ran back to find the old wolf sitting on his mound, crying in a soul-crushing kind of disconsolate wail. And then it ended, and that was all.

A month later, the alpha male took the old wolf’s place on the mound and stayed there for a month. He didn’t get up to go anywhere. I can’t explain it, but it seemed like a memorial. I’m afraid of anthropomorphizing here. I can, however, imagine some possible explanations. The smell of death is a very serious thing for animals. They don’t fear death. They don’t even know what death is. The smell of death, however, when a wolf is dying and before the end comes, is a source of panic and terror.

-Some people say that wolves eat the sick and old of the pack. Is there any truth to this?

-Those are all old wives’ tales. The young often die of injuries sustained in fights. They lose too much blood or their wounds get infected, and then they get weak and can’t move. Only about half of a litter lives to one year of age. Despite this, they never kill each other on purpose. Anything you hear about cannibalism is pure embellishment. It occasionally comes to that, of course. During the Siege of Leningrad and the famine in the Volga Valley, you also had children eating their parents and parents eating their children.

In reality, they have an amazingly well-developed system of mutual support. They even saved my life. We were returning from an incredibly unlucky day of hunting. We lost several deer, and there were other problems. We had been dragging our feet all day and into the evening. The wolves were tired, and you can imagine what condition I was in. About five kilometers out from the rendezvous site, there was a huge boulder. I walked up to it because I was at the end of my strength and needed to sit down. Then a bear came out and reared up. I was as close to the animal as I am to you right now. I can’t remember if I screamed or he made a sound, but the wolves heard and all came rushing in, even though one blow from a bear’s paw could tear a wolf to pieces. But “the poet’s soul could not endure” once a she-wolf grabbed the bear by the heel, and he tumbled down the hill.

That was the first time I really had thoughts about altruism. What is it? This means it is the realization of a biological necessity. A beast doesn’t think about the consequences. I then understood that everything we have, everything we’re proud of, is not the product of our invention, but comes from this aspect of nature… It’s interesting that the adults don’t defend the cubs from humans. They understand that it’s more important to keep themselves alive as breeders than to save a litter from death. This is cultural development. They defend their young from all other animals, such as lynxes or other wolf packs.

-Do wolf packs attack each other?

-It happens occasionally, whenever there’s a turf war. That happens when sources of food on a territory are exhausted for some reason. As a rule, this is due to human expansion.

-Did your wolves howl at the moon?

-They don’t howl at the moon, but the full moon lets loose a flow of emotions.

-Why do they howl?

- This is the way they communicate with other groups. It’s social contact across the distance. Furthermore, it provides important information about how far away animals are, about status and the emotional state of the pack. Each member has its own part, and, as far as we can tell, each howl has a function.

-How do they know how to howl?

-There are two categories of sounds. Inborn sounds provoke inborn responses. For example, the sound for danger is a sort of cackling bark. The cubs hear it, and they all run away, even though nobody ever taught them how to do it. Then there are the learned sounds. There are dialects. A wolf from Kahetia, in Eastern Georgia, would be unlikely to understand a wolf from Western Georgia. I was once in Canada at the request of John Teberge, and we went to a national park. I started to vab (give a greeting howl), turning about and going “Ul-lyu-lyu” in the Georgian way, with a few flourishes. The Canadian wolves couldn’t have cared less, and it really upset me. Then Teberge went “oooo” just like a clarinet, and the wolves all went crazy howling in response.

-What do you mean by “flourishes”? Are these words the wolves say to each other?

- If I could understand, I’d put together a dictionary. I’m also terribly interested in these questions, but, unfortunately, there’s no possibility of studying it. They can express all sorts of information. I, for example, found that when the parents call their young to the site of a kill, they can use their howl to clarify how to get there. There are paths that can’t be followed directly. The alphas go to the turn, howl, and the cubs hear. Then they go on to the next stop and howl again. In four or five months, the cubs already have it down, the zigzag is in their heads, and they can find it easily. There’s a howl to gather the pack whenever the group wanders off and the wolves miss each other. That’s an easy sound to differentiate from the others. It fills the air with such an anguished melancholy that it rends your soul. Honestly, there are many views on the matter, but very little is clear. There’s a man called San Sanych Nikolskiy in Moscow, and he knows this subject better than anyone, so ask him.

-So you hung out with them for two years, without any break?

-No, when you’ve stayed about three months in the woods, the soul demands some kind of human communication. I periodically returned home to Tbilisi for a few days. I couldn’t stay away much longer than that, so as not to lose touch with my pack.

-And you had children at this time, is that correct?

-Yes, I had young children. The kids grew up with wolves in the apartment, and everyone made a fuss. I was something of a spectacle because all the normal zoologists were studying more common animals. “How can you study an animal that you can’t eat? You ought to study deer!” They were all sure that I would somehow make some money off of my wolves. Maybe I would kill them and sell off their furs. They couldn’t think otherwise. The pay was one-hundred forty rubles a month, but the prize for a wolf was fifty. Somebody naturally sent the financial inspectors, who asked where the cubs all went. The cubs often die. So I told them that I had buried them. How could they believe that I had simply buried all that money? It came to digging up the poor rotten corpses to show off the untouched fur. I was making money in other ways. I did embossing work and made jewelry. I did a lot of silver work under the table, and did some work as an auto mechanic. The pay was never enough, of course, in order to work with captive animals. You have to feed them meat, after all. What else could I do? I had an irresistible urge to study this subject.

-How did it end with the wolf pack?

-It isn’t possible to settle with them forever. I would happily do so, but it’s impossible. I returned after a year away, and it turned out that fifty-four wolves had been killed, including my pack. That was very difficult to deal with.

After that, the reserve was overrun with feral dogs, because there was nobody else to fill the space. I later joined myself to other packs, five in all, but the first was always the most important. There was more distance after that, and, honestly, it was less interesting. They generally followed the herds of sheep between winter and summer grazing areas. Psychologically, they were completely different beasts, and their lives weren’t interesting.

-So you started to breed your own wolves?

-Yes, in the course of things, the idea of reintroduction entered my head. At first it came as a way to save the animals I had experimented with. We had to do something with them, kill them or give them to a zoo, just get rid of them somehow. We needed to let them loose somewhere. It was clear, however, that a beast raised in captivity couldn’t survive in the woods. On the other hand, there are many species that can no longer exist in nature, so it’s a problem everywhere. Leopards have completely disappeared from the Caucasus. There are hardly any more spotted hyenas. So we need to get births in captivity and set the mature young free. Think about it, though. You’ve been in zoos, and right away, you see the psychological damage of captivity, such as nervous tics and repetitive movements. I decided to raise these beasts with normal predatory behavior, in order to survive in the forest.

I wrote classifieds in newspapers, started buying cubs from hunters to feed them. I bungled my first two attempts, unfortunately. I took in suckling cubs, whose eyes were entirely closed and undeveloped. Apparently, for them to grow up correctly, you need to know how to feed them correctly. You need to know what kind of nipple there ought to be, and what kind of hole in the nipple. For example, during suckling, the cub needs to kneed the mother’s mammary gland with its paws, up and down. The flexor and extensor muscles work in turns, and they send impulses to the brain. If there’s nothing to lean against, it causes tonic muscle tension in the flexors and extensors. This brings about hotspots of high activity in the brain that remain for the rest of their lives. The animals grow up psychologically unbalanced, suffer from frustration and depression, and get into group conflicts. There’s inadequate tactile activity in the paws, and that makes it hard for a wolf to live.

Then it turned out that it was bad to have too big a hole in the nipple. The cubs’ stomachs fill up fast, but their young brains still aren’t fully formed. They feel neither hunger nor satisfaction, and stop only when they have fulfilled their instinctive demand for suckling. This has no connection to the stomach. The milk pours out, their bellies swell up, but they just keep sucking. Then their stomachs expand, and increase their potential volume. When they grow up, they need more food than the others and get hungry more quickly. The wolves enter a state like bulimia, where they can never eat enough. They behave in a way that destabilizes their position in the group. Aggression in such wolves never becomes ritualized, and they can’t form healthy relationships… But how could I imagine all of that? I only understood it all later on.

-It seems that a living being is honed to its surroundings: one step to either side, and it all falls apart…

-That goes without saying. I think that Leonardo da Vinci said it first--no organism exists on its own, but lives within its surroundings, and all of our research should be built upon this connection, or else it will remain an isolated artifact. It’s so important, therefore, to gain field experience.

Naturally, the boundaries are especially narrow for newborns, and adults are more flexible. You need to get it somehow, and, thank heavens, I seem to have gotten most of it. I fed the wolves at home, and as soon as they started to move around, near the time they would leave the den, I took them out to the open fields for a couple days. I let them loose when they were still only half-mature, on the Trialeti Ridge near Tblisi. I stayed with them there. I wasn’t there all the time. You stay pretty close, and return often.

-How did you teach them?

The most important thing is for them to form orientation and special skills. They need to know the territory on which they live, the main trails, and the watering holes of hoofed prey. They can’t hunt without knowing that. Later on, they need to learn to follow a trail. Let’s say they’ve found the trail of a deer. The wolves have a sharp reaction, because the deer have a very distinctive smell. You must call them down when this happens. I was still learning to follow tracks, sniff around, whine wolfishly and call to them. They came running without fail and did the same. That’s how their parents teach them. Let’s say the track becomes dangerous. The mother will demonstratively sniff about, and the wolves scamper after, also sniffing until she gives the signal for trouble. That’s the cackling bark, which is the same in all wolves and sets in motion a natural reaction in cubs. They scatter in all directions. They will never follow that trail again in their lives. That's how I learned to bark. The noises that positively reinforce situations, however, I cannot reproduce. It must be some failure of my hearing.

-But you couldn’t sense things like they do, could you?

-Sometimes I’d react to their reactions. There would be some kind of sound or smell that I didn’t get. You don’t even have to understand--the most important thing is to react and look in the same direction. Then you see the results. Their eyesight suffers from this method, however, and they get near-sighted. I noticed that one day in autumn, during quail hunting season. When I stood against the wind, they couldn’t tell the hunters from me. Then they threw themselves at a hunter, who panicked, and I shouted “Don’t shoot!” as the hullabaloo went on. Then they figured out that it wasn’t me, and flew right past the hunter, snapping up the quail that was hanging from the hunter’s side. What could you do? I couldn’t wear brighter clothing, or I’d scare off the other animals. It’s good that nobody wore a beard in Georgia at that time, except when a close relative died, and they didn’t shave for 40 days. I had to grow out my beard.

-Did you teach them to hunt?

-Yes, and I taught them exactly what I had seen. I went in sneakily, like a poacher, and shot roe deer. At first, I just gave out the meat. I bought stomach acid as sold in pharmacies, poured it out on the meat, let it ferment, and gave it out as half-digested, just like from mama. The cubs, as it seemed, couldn’t get enough of it. Then came raw meat, then in the hide, throwing them a leg or some such. Later on, I’d bring them half-finished deer. I had shot it with a tranquilizer dart. When it started to come to, I set the wolves on it.

-You couldn’t replace the traditional pack, and teach them to chase and attack, could you?

-The most important thing was to motivate the young wolves, and inspire their interest. I was their chief, their dominant alpha male, but they did everything themselves. All they need is one successful hunt, then everything gets sharp on its own. Mainly, they need to know how to look in order to hunt.

Besides that, they need to learn how to think. They start thinking at about five months. They are always playing at chase angles, and they can extrapolate the movement of potential victims, frankly, in order to cut them off in their tracks. It doesn’t work out for them so well to start off with. If a partner hides from view behind a rock, the others redundantly follow his path. They work this out in about another five months. Later on, in experiments, it became clear that at precisely this age, they become capable of using past experience to apply it to conditions in a logical way.

It’s interesting that under experimental conditions, the animals dealt with these tasks poorly. They decided to break away sooner, and started to slack off and snap at us. That’s because thought requires strong nerve pressure. How do they hunt then? During any given hunt, a wolf is required to complete dozens of different extrapolated tasks, and they never fail despite the high emotional pressure. Why? My deceased teacher, Krushinsky, and I spoke of that often.

It turned out that animals raised in captivity, in a stimulus-impoverished environment, could not normally develop an ability to think freely in a normal way. I had two groups of cubs. I raised one in a typical zoo cage, and another in a cage with an enhanced environment with plenty of boulders and tree trunks they could hide behind. In seven months, the cubs from the enhanced cage could complete a complex task, but the wolves from the usual cage could not. Then, at one year, I switched the wolves’ places, but the wolves from the typical cage were already incapable of thinking in a healthy way, and the ability was gone. They could complete one or two of the complex tasks, and then they quit. The wolves from the enhanced cage just clicked and had no problem. Why? It seems there are two levels. You can’t really talk about wolves having a consciousness and sub-consciousness, but it’s something like that. If a beast has no experience with extrapolation, it has to use some kind of “conscious” reasoning to deal with the problem, and then it is very difficult. It’s like the multiplication table: If you teach it too intensively, the child will react with hatred. If you pile up the simple lessons gradually, in game-type situations, then the learning occurs at a subconscious level. Like driving a car or playing the piano, completing the task itself doesn’t cause any emotional tension.

-That brings to mind a classic lesson from child psychology…

-Yes, of course. There are few real differences between us in this regard, because the problems of our lives are similar. We spend our whole lives learning to live…

In the end, I set both groups of cubs loose on Trialeti Ridge and tried to teach them to hunt. The lessons clearly didn’t work with the animals from the normal cages. The deer weren’t afraid of them at first, but then there were some other problems, and it all fell through. It’s a shame that I raised them inadequately, and I did this to them on purpose. I knew that they would have to spend their whole lives in captivity.

The other group, however, learned their lessons wonderfully.

-Was there a moment when you knew for certain that they had figured everything out?

-I was lucky. There weren’t any wolves on that mountain when we arrived, only feral dogs. The roe deer had adapted to the presence of the dogs, and knew that they were predators. Wolves have a different smell, and a different look, so the deer let them in close.

Animals have an understanding of “running distance,” which is the minimum amount of space they will allow between themselves and others. You can use this to easily understand the level of poaching in an area. Whenever I go to national parks in Switzerland or America, I almost get sick of all the animals, because they’re always running around right in front of you. Over here, they won’t let you inside of five-hundred meters…

Well, the roe deer weren’t afraid of the wolves, so the likelihood of a successful hunt shot up to 50 percent, which is very high. That, honestly, saved the whole project. Then the running distance began to go up, and the success level went down.

-I’ve heard that you taught them not to eat sheep. Is this true?

-Yes. What’s the biggest problem with reintroduction? Issues with the local human population, that’s what. These animals don’t fear people. They’ve been releasing cheetahs into the wild in Africa for many years now, and whenever it’s too hard for them to find large grazing animals, they go into villages and steal sheep and chickens. The people start killing the cheetahs, and you have to gather them back up again. If the local population is against a program, that’s the end of it. Furthermore, the level of poaching in the former USSR is astounding.

I know wild wolves, and they avoid humans like the plague. So I had to somehow teach my wolves to do the same. Back in the sixties, there was a great Spanish physiologist by the name of Jose Delgado, who thought up a way to make money with a show. He put an electrode in a bull’s brain and held on to a controller. Whenever the furious bull would charge at him, he would press a button, and the bull would stop dead in his tracks at half a meter away. I didn’t want to put any electrodes in the wolves’ brains, so I thought of using a shock collar. It was good that by that time the super-duper flat-cell batteries had appeared. In Tbilisi, you could buy everything from army officers. I picked up some at nine volts, but there were 300 volt shockers available.

We involved the local residents, because it was impossible to hide our work. If you can show the townsfolk that the wolves are afraid of them, they’ll simply be ecstatic. From there on out, the relationship changes entirely. We needed lots of different people for this: old, young, hunchbacked, with bags, without bags, with sticks, with guns, and so on and so forth. The wolves had gotten used to me, so, through generalization, they did not fear any human. So a new person would show up, the wolves would approach, and I would press the button, sending out the electric charge. We did it again, and again, and again until as soon as they saw a human, they’d run off in a second. At first, they wouldn’t run too far, so we had to work on creating the kind of reaction that could save their lives. They needed a running distance that was beyond the range of gunshot. Overall, we needed about forty days to get it all worked out perfectly.

We had to condition the wolves to react to domesticated animals in a similar way. The shepherds agreed to this eagerly, and they were very curious as to how a wolf could fail to eat a sheep. That was crazy. You ought to have seen the look on the sheep’s face when a wolf ran away from it. By the second time, the sheep was already looking down on the predator: “What a wimp!” The farmers had the same reaction, and they loved it.

This reaction, however, doesn’t generalize across all breeds of livestock, so we had to go through all of this again with goats, cows and horses. While this was going on, one she-wolf crept off to a sheep shelter, where they also kept chickens. She ripped apart a chicken, but didn’t touch the sheep.

-The same sort of shock collar is already on sale in Moscow.

-Yes, I foolishly published an article where I described everything. None of us figured that in two years, over in America, the so-called “electronic dog trainer” would show up. I had one more invention: I hung a small radio transmitter on the wolves, took their bearings and could make an exact map of their movements. I put the ping machine together myself, and it worked at up to five kilometers. I didn’t want to go running after them whenever they went to another place. The military caught my signals, because they were pinging in the area. I didn’t have any quartz stabilizers at the time, so the frequency changed in sunshine or in shade. The army would get an ee-oo-ee-oo signal, and they thought somebody was trying to send a coded message. They held me in detention in the back of a truck for three days, while I plead with them:

“Listen, I’m a zoologist. Do you want me to call the wolves?”

And they replied: “Are you trying to trick us? Do you take us for fools?”

Well, by the third day, somebody got the message, and the colonel came in and asked: “What are you doing?”

And I said: “I’m from the institute of zoology, and I’m following the movements of wolves.”

“How can you prove this?”

I answered: “Let’s get out of here, go about a hundred meters out. I’ll howl, and the wolves will come.”

He just stared at me, squinting and must have been thinking that I was absolutely full of crap and just kept piling it on. But we went out, I howled, and the wolves came out of the forest to meet us. The officers were horrified, and it’s good that they didn’t shoot. They made me take off the collars, which they then took away. I only had one chance to try this.

-So you taught them to deal with everything. What happened next?

- Further on, it was interesting to see what happened with the next generations. I was sure that they had taught their cubs on their own. Even the first generation of cubs ran away from me when they first saw me. That’s because whenever the alpha female saw a human, she would let out the cackling bark, telling them to run off. Then she saw for herself that it was me and wanted to communicate, but the others were afraid. I still wanted to see what came next. I made every metal collar out of steel plates. On each one is an inscription saying that if you bring me this collar, I will pay twice what the government will. Nobody has brought me a single one. I asked about it later on, and over ten years in those areas, there hadn’t been one wolf killed, and none of the local hunters had seen them. That means that a tradition has been established, and the elders are teaching the cubs.

-Has this method been applied to any other species?

-This method fits tigers, leopards and all large predators. It was of great benefit to work with wolves, because they are the most complicated in their psyche and social organization. If you gave me another chance today, I would have done it all differently. I wouldn’t have fed the wolves so much, or gone through so much horrible fuss. I’d set them up with a she-wolf who I had taught. That’s the same way shepherd dogs raise their pups. I now know that that comes across perfectly. You can work with two or three alpha pairs, and they will teach the cubs everything themselves.

-Did you follow your pack for long?

-I observed them for four years. I’m still not sure that everything is fine with them.

-Did you ever see them again?

-There was an odd story after all of that, about nine years later. I went to the ridge on my own business, walked about the woods, and I saw a familiar track. At first I wasn’t sure why it was familiar, but there was a toe missing. I knew that they were my wolves. I walked around for a week, vabbing. And finally, here they came—two wolves. They were already thirteen by that time, gray and with missing teeth. I was nearly sure that they couldn’t hunt for roe deer any more, but rather fed on hares and rodents. Thinking back on it, they must have been circling me for two days, observing me. They finally came out, very tired, and looked at me, kept looking, then started to play like little cubs. Oh, how they played and yelped! I’d never been so happy in my life.

This interview appeared in slightly redacted form in “Russkiy Reportyor.” The photos of Yason are by Mikhail Ioshpa yazim. The photos of wolves are by Yason Badridze.

Yason is an intelligent, simple and charming man. He looks much younger than his sixty years. You can see that he has spent half of his life in the forest. Speaking with Yason brings about a strange feeling, as though simply through communication you were transported into nature. The feeling comes straight through him. For the last year and a half, Yason has stayed at his apartment in Tbilisi. At dawn he takes a jeep around the surrounding mountains, observing packs of dogs and metis (half-wolves, half-dogs which have multiplied there). He sometimes takes students to the forest. He has nothing else to do, since the scientific base is in Russia (The A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution), and he cannot obtain a visa. During this period of idleness, Badridze took it upon himself to write his memoirs.

PS In the sub-headline of this interview in the “Russkiy Reportyor” I called Yason “a cult figure among ethologists,” after which I received this letter from him:

Hello, Shura! Don’t be surprised at this letter, but I’m very troubled by one thing. It’s very pleasant to see the general reaction to the interview, but there is something else that bothers me. Several sites have showed up with the title “Cult figure among scientist-ethologists”…First of all, Conrad Laurence and Niko Tinbergen (among others) are “cult figures” among ethologists. Second of all, this way of thinking is incorrect, at least as concerns my colleagues who are truly gifted ethologists. Third of all, even if I am considered a scientist, I haven’t been able to do (for whatever reason) even half of what needed to be done.

I therefore may have the boldness to ask you to pass along to your reader my attitude toward those epithets.

Thanks ahead of time,

Yason